Abstract

The growing ubiquity and impact of misinformation has stimulated research on fact-checking and fake news classification. This research has drawn upon many fields such as Natural Language Processing, machine learning, and journalism in an effort to efficiently identify and mitigate the spread of misinformation. As part of this ongoing effort, this project provides two Recurrent Convolutional Neural Networks that assesses the truthfulness of an article or claim, both achieving overall accuracies of over 90%. While the performance of our models demonstrate promise, it is wise to consider how other researchers and scholars tackle the task. As such, we also provide a discussion on relevant considerations regarding the tasks of fact-checking and fake news classification. We conclude with a discussion of ethical considerations with the deployment of fact-checking and fake news classification systems, making suggestions and reflecting on the state of the field.

Project Members: Chira Levy, Hussein Faara, Jorge Rodriguez

Introduction

With the advent of social media, many barriers required to publish information are effectively removed, granting many individuals and organizations the ability to rapidly disseminate information to reach mass audiences. It is no surprise, then, that this enhanced ability can be used to spread true and false information, and has become an important concern, fueling a growing demand for the fact-checking of online content.

In journalism, fact-checking is the task of assessing the validity, or veracity, of a claim. It is a task that is usually performed manually by trained fact-checkers: typically it entails verifying whether a piece of text or claim is accurate by utilizing relevant information from various trustworthy sources. This procedure can be very time-consuming depending on a couple of parameters, such as the complexity of the claim and the evidence needed to provide a verdict. With online news outlets on the rise and an increasingly engaged global social media base, there is a growing need to fact-check and detect potential loci of misinformation (e.g. fake news) found in information providers across the internet in a more efficient manner. In fact, in 2020 alone, fake news websites significantly increased their share of engagement on social media platforms making up nearly one-fifth (17%) of all likes, shares, comments – a stark contrast to roughly 8% in 2019 1. These figures bear significant importance as interactions with fake news and fake claims on social media can potentially exacerbate political polarization, quickly skew opinions, and negatively influence how people perceive crises – for example, the ongoing SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. This raises the question: what can be done to help journalists and trained fact-checkers address and mitigate the fake news and misinformation problem? Enter fact-checking and classification.

Fact-Checking can be traced back to 2011 when scholars Cohen et al. suggested it as one of the tasks that should (at the very least) be aided by machines, or automated since the relevant technology begins to suggest the possibility. Later in 2014 the task is not only introduced by Vlachos and Riedel but they also compile a dataset and propose an end-to-end algorithm suitable for completing the task. Subsequent research over the past 6 years has demonstrated the popularity of the task. This rise in popularity is partly due to the progress made in relevant fields like natural language processing (NLP), information retrieval, and increased access to robust data(sets/bases).

As part of the ongoing discourse in the field, this project attempts to provide a comprehensive overview of the state of the field, as well as address what is a significant lack of oversight in quality filters of social media companies by taking a more deliberate approach in classifying what is misinformation and what is not. Using a neural network classifier trained on recent datasets, our goal is to flag articles that either intentionally or unintentionally include untrue statements about COVID or COVID-related topics.

We aim for at least 85% accuracy and specifically less than 7.5% of false negatives (news classified as trustworthy when not). A technical challenge we will face is the reliance on the data used to train our classifier. Most, if not all, of the state-of-the-art fake news detection systems rely on data that could easily be converted into a vector and fed to a model.

1 Sara Fischer. “‘Unreliable’ News Sources Got More Traction in 2020.” Axios, Axios Media, 22 Dec. 2020.

What is Fact-Checking?

From a researcher’s point of view, Vlachos and Riedel define fact-checking as “the assignment of a truth value to a claim made in a particular context.” Traditionally the task has been commonly performed by trained professionals. In fact, a trained fact-checker must consolidate previous publications or known facts, combined with reasoning, to reach a verdict on an article before publishing it. Due to the large amount of content produced and shared each second on online outlets and social media nowadays, false information spreads at an unprecedented speed. The time-consuming traditional method of fact-checking is clearly insufficient. Fortunately, rapid progress in the fields of natural language processing, databases, and information retrieval over the past decade has made delegating the task to machines more plausible. Therefore, apart from attempting to accurately assess the truthfulness of claims, automated fact-checking attempts to reduce the human burden of assessing such claims.

Although what an automated fact-checking system should do is intuitive, several scholars have framed it in different ways. For example, Vlachos and Riedel highlight that it is not necessarily a binary classification task because many statements are neither completely true nor completely false. As a result, some fact-checking datasets label the claims with varying veracity levels. According To Hassan et al., an ideal automated fact-checking system should not only be able to make accurate assessments, but should also be fully automated, instant, and accountable. This is a very challenging task because it requires solving the often difficult computational problems of natural language, understanding context, retrieving relevant information, and reasoning. Furthermore, an ability to explain its decision with supporting evidence from trusted sources is generally expected of any good automated fact-checking system, complicating the task even further.

Methods

There is a tendency in people to conceive what they read from news sources and/or social media sites to be completely true – even if the news source admits to their mistakes retroactively. It is important to identify fake news from the real news and/or check whether claims made are valid or not – especially during our protracted times with the SARS-COV-2 virus. This problem can be tackled with the help of Natural Language Processing (NLP) tools which can aid in identifying fake or reliable news based on historical data. The following is an outline of how we constructed our classifier and the datasets we utilized in the training process.

Our Classifiers

Per traditional NLP pipelines, we first converted tokenized text from our dataset to tensor representations using pre-trained word embeddings. Here, we use a Global Vectors for Word Representation model (GloVe), specifically one which represents words as 100 dimensional vectors. We chose GloVe over other word embedding tools such as word2vec since it does not rely solely on local statistics (local context information of words), but utilizes global statistics such as word co-occurrence to obtain word vectors. Given COVID-19 news, fake and true, is produced worldwide, this global property of GloVe felt more appropriate for our classifier. That said, word2vec and GloVe, as two of the most popular tools to generate word embeddings, share many similarities so the decision to go with one over the other was inconsequential.

We then fed these word embeddings into two recurrent convolutional neural networks we constructed using Tensorflow’s Keras python library. ( We chose these libraries to ensure proper understanding of our classifier’s function and to ease modifications when deemed necessary.) Within these classifiers are several different types of sequential operations and layers. These include (any strategic arrangement of) convolutions, max-pooling layers, Long Short Term Memory (LSTM) layers, dropout layers, bidirectional layers, and fully connected layers.

Preliminary analysis on the dataset suggests that the average article length is 415 words and the median length is 371 words. The distribution is right-skewed with 75% of the articles having a word count under 525 words and the longest article’s length is an outlier containing 8436 words. For the purpose of our models, we will base off the dimensions of our layers on this and other pertinent relevant data.

Our first classifier embodies an architecture as follows:

- An embedding layer that takes as input 100-dim embedding vectors representing each unique word in our text and generates a 512 by 100 embedding matrix optimally mapping these words such that similar words have similar vectors. We designed this layer such that it expects a 100-dim vector as that was the size of the initial pre-trained word vectors we used from GloVe.

- A 1D convolutional layer with 64 filters and 5 kernels of which is preceded by a dropout layer with a rate of 0.2. Convolutional layers have been shown to improve performance in NLP tasks, particularly due to their ability to extract relations between non-adjacent words. We include one here for this reason and immediately follow it up with a dropout layer, for studies have shown a positive effect of applying dropout to convolutional layers. Our dropout rate and number of filters here were selected in an effort to minimize computational processing but maximize accuracy.

- A Max Pooling 1D layer with a pool size of 4. Per convention, this layer was placed shortly after our convolutional layer to compress the massive feature space, but maintain significant features. A 2 x 2 (4) pool size is default for max pooling layers.

- Two Long Short Term Memory layers (both of which have 20 neurons) followed by a dropout layer with a rate of 0.4. LSTMs have proven extremely useful in NLP tasks and are incorporated here as such. Given their intrinsic efficacy, the size of these layers were chosen modestly. The dropout rate was experimentally determined.

- Two fully connected (FC) layers (512 and 256 neurons, respectively) each of which were preceded by dropout layers (0.2 and 0.3). We begin to wind down our network with FC layers which take the features extracted by the prior layers and begin to classify them. Increasing the size of these layers beyond a certain threshold was inconsequential in improving the accuracy of the network. 512 and 256 were beyond this threshold.

- Lastly, there is a FC layer using a sigmoidal activation function to output either a 0 or 1, i.e. Fake or Real.

Our second classifier has the following components:

- A embedding layer that analyzes a 64-dim embedding vector for each word in the article. Most neural networks have embedding sizes of 128 but, after experimenting, we found an embedding dimension of 64 to be optimal. It aggregates the vectors for the first 512 words (following the above dataset article length analysis) in order to generate an embedding matrix of the shape [512, 64] for each input article.

- Three pairs of convolutional and MaxPooling1D layers. The convolutional layers have 128 convolutional filters and a kernel size of 5. It is followed by the MaxPooling layer with a pool size of 2. By having 128 convolutional filters, the neural network will intuitively have three sets of 128 features it can learn. This value came to be in an experimental and iterative manner.

- Two pairs of Long Short-Term Memory layers (equipped with 128 neurons to match the number of convolutional filters in previous layers) with each LSTM layer followed by a Dropout layer of 10%. Dropout values of 50-80% seem to be common, but in our experiments a Dropout of 10% yielded optimal results.

- Finally, a fully connected layer that uses the sigmoid activation function, outputting a single value between 0 and 1 to indicate the probability of an article’s truthfulness.

In regards to the training of the model, we use a binary cross-entropy to calculate loss and ADAM to handle optimization— an increasingly default setting for model training.

Datasets

The following datasets were useful in our experiments:

- Fake News Data

- COVID-19 Fake News Dataset 1 (Supplemented by COVID-19 Fake News Dataset 2)

Our classifier was trained on a general dataset (the first linked dataset above) of news articles that fall under two labels: Real or Fake. We performed some preliminary analysis using the Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) module from Scikit-learn and the pyLDAvis library to compare topics and most significant terms in real and fake news articles.

Discussion

The bulk of our project attends to the first dataset enumerated in our “Datasets” section. To better understand our dataset, we think it is important to consider the distribution of fake news versus real news, the length of articles, and even the topic breakdown of the articles sourced from the datasets we selected for this project. Other metrics that allow us to understand topic coherence between real and fake news are Perplexity and Coherence. The former measures how probable new unseen data is given the model that was learned earlier. That is to say, how well does our model represent or reproduce the statistics of the held-out data. As a rule of thumb, a lower perplexity implies that data is more likely. The latter (Coherence) measures the degree of semantic similarity between high scoring words in a topic. Therefore, the higher the coherence the higher the semantic similarity between words.

Our first dataset was composed of a total of 44,898 articles with meta-data such as the title, topic, publishing date, and the corresponding label included. Within this data, there was a 1.1:1 ratio between real and fake news articles. Upon further inspection of the articles, we constructed a topic model using LDA.

Understanding Latent Dirichlet Allocation Topic Modeling

Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) is one of many algorithms used to perform topic modeling. LDA’s approach to is to simply consider each document as a collection of topics and each topic as a collection of keywords. Each keyword within in a topic contributes a certain weightage, or importance, to a topic and the number of topics to begin with is determined by the developer. Adjusting this number rearranges the topic distribution within documents and thereby the key word distribution within those topics.

Visualization

Here, we visualize topics using an interactive chart provided by the pyLDAvis package. Each circle in the chart represents a topic and the size of each circle corresponds to the relative prevalence of that topic in the corpus. The distance between these circles represents how semantically different the topics are from each other.

Upon first inspection, you will see that the words on the right side of the screen will be ordered, not by frequency(blue bar), but by their salience. Saliency is a metric used to describe how general or specific a term is in the context of the topics generated by the topic model. The most frequent words in the collection of documents that are assigned to the fewest topics will have the greatest saliency scores. The purpose of this metric is to help identify which words are the most informative for distinguishing the topics. This metric’s formula is shown on the bottom right.

Interaction

If you hover over any word on the right, you will see the circles that have relatively high frequencies of that word increase in size. As you do this, you might also see other circles decrease in size or disappear. This means those topics have relatively lower frequencies of that word or do not have that word at all.

If you click any of the topic circles on the left, you’ll see a list of the most relevant words for that topic appear on the right along with their overall frequency (blue bar) and their frequency within that selected topic (red bar). It is important to acknowledge that these words are ranked according to relevance, not frequency. Unlike frequency, relevance is used to identify the most important words for a given topic. At the top you can adjust this metric to your liking. A lower number displays words more exclusively assigned to that specific topic and a higher number displays more general/common words in that topic.

Interpretation

A “good” topic model will have large, non-overlapping circles dispersed throughout the chart (i.e. not in one quadrant).

A model with too many topics, will typically have many overlapping, smaller bubbles concentrated in one region of the chart.

How “good” a topic model is often depends on the number of topics you choose, however, sometimes you may have a optimal number of topics, but your visualization may look poor simply due to the nature of the text. Your visualization is ultimately influenced by the number of topics parameter as well as the size and type of corpus you have.

Assuming we chose an optimal number of topics, this visualization helped us gain both a qualitative and quantitative understanding of what topics and specific keywords our data are concerned with and to what extent.

Interestingly, we found that our real and fake articles were relatively the same in terms of topic coherence with real news at 0.42 and fake news at 0.47. In terms of perplexity, both real and fake datasets produced negative perplexity scores (-8.21 and -9.1, respectively), though our fake news set was slightly lower. One interpretation of these intrinsic evaluation metrics is that the fake news dataset is relatively more consistent given the redundant and uninventive properties of traditional fake news. These characteristics are represented in the fact that the circles that represent topics in our fake news LDA are closer together/overlap more than the topic circles in our real news dataset. Most interesting, perhaps, is that the real news is much more varied across topics, ranging from international affairs, weather-related reports, domestic and international commerce, the economy, and (of course) politics. In contrast, fake news focalized political matters which are not out-of-character with traditional fake news articles.

In order to evaluate the performance of this model effectively, we split the data into separate training, validation, and testing sets.

- 56% was used for training

- 14% was used for validation

- 30% was used for testing

Our two classifiers, though having different architectures, perform relatively the same with overall recorded accuracies of 99% each. With that said, while accuracy is a useful metric to assess the performance of a classifier, it fails to tell us how the model is performing relative to each class. To have a robust understanding of our classifiers’ performance, we also created confusion matrices to understand the distribution of true positives, false positives, false negatives, and true negatives.

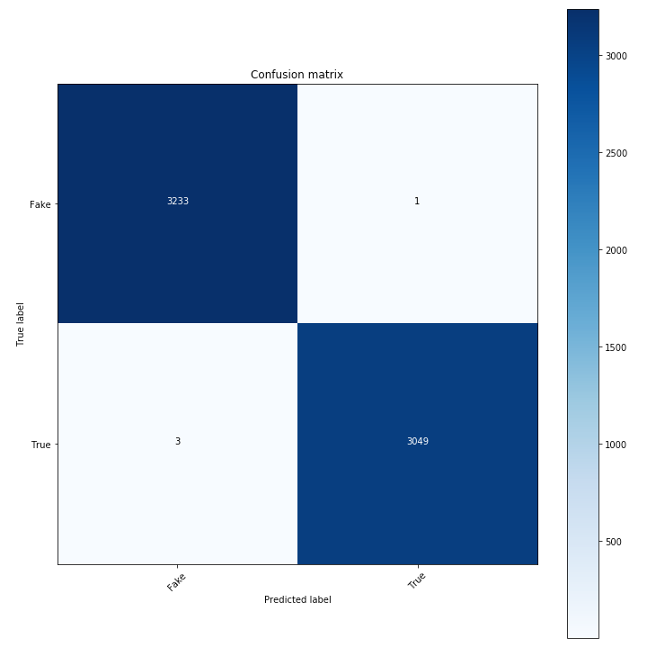

Model 1

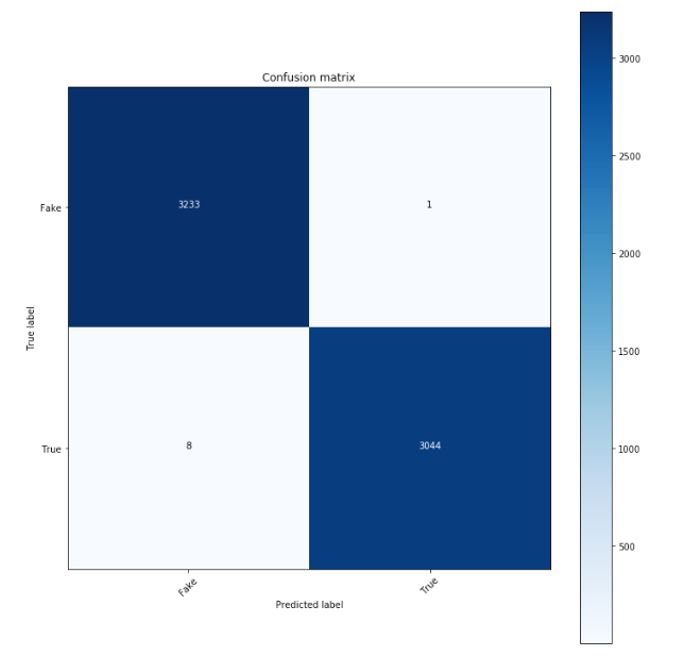

Model 2

Both models had 1 false positives, meaning that they misclassified one fake news article as real news. But they differed in their numbers of false negatives. The first model had 3, meaning that it misclassified 3 real news articles as fake news. The second model on the other hand had 8 false negatives. These behaviors were reflected in our classification report, which is a report that centered around a model’s performance with respect to the validation set, and it also gives us the following metrics:

- Precision — the number of times a class was correctly predicted divided by the total number of times the model predicted this class.

- Recall — the number of times a class was correctly predicted divided by the total number of samples with that class label in the testing data.

- F1-Score — the harmonic mean of precision and recall.

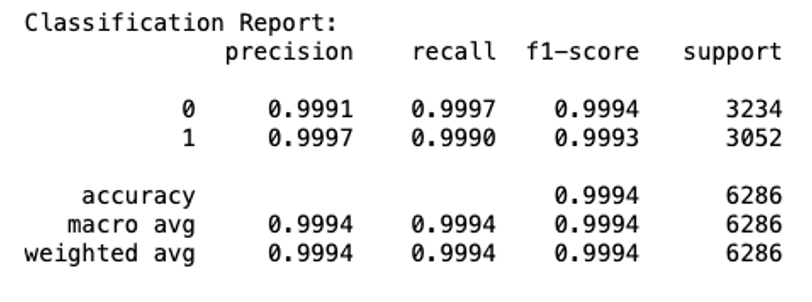

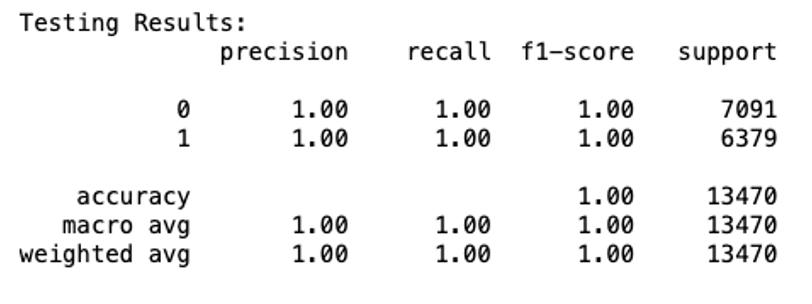

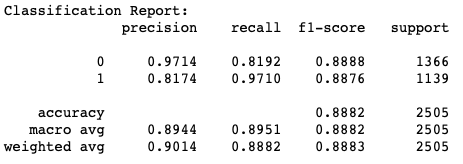

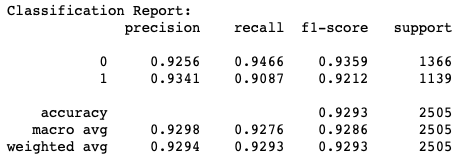

Model 1

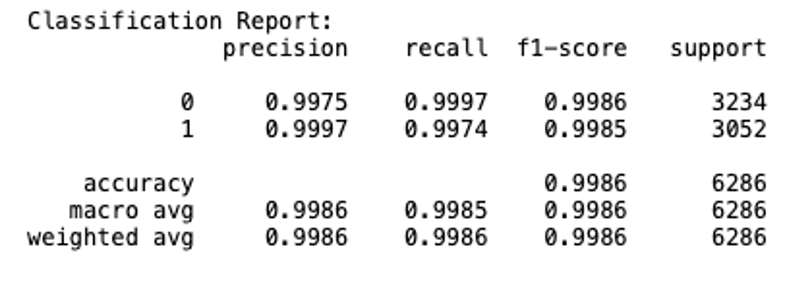

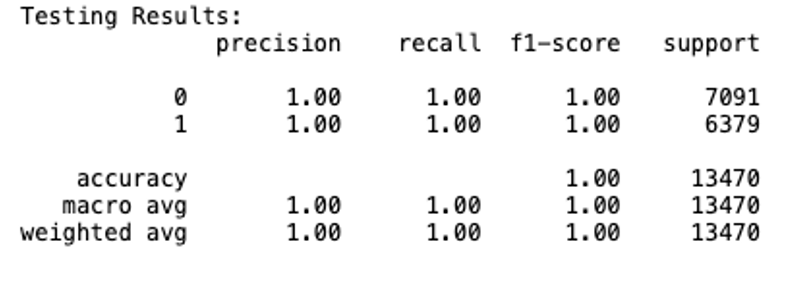

Model 2

Based on these results, we can see that the models are nearly as good at detecting fake news correctly as it is at detecting real news correctly and achieved an overall accuracy of 99% on the validation data, which is pretty impressive. While the validation results can give us some indication of the model’s performance on unseen data, it is the testing set, which has not been touched at all during the model training process which provides the best objective and statistically correct measure of the model’s performance.

Model 1

Model 2

Based on these results, our models for the general dataset indicate that both models are equally adept at detecting fake news and real news, both achieving an overall accuracy of 100% – this is truly remarkable!

Extending to COVID Dataset

In our COVID dataset(s), we ran all of the above analyses for the same reasons, save a few exceptions. One distinctive difference between our first dataset and our COVID one is that the latter only contains titles, meaning our classifier must deliberate the validity of an article title/claim using significantly less text. Another difference lies in the fact that our COVID dataset had a relatively greater imbalance between real and fake news articles. But we were able to control for this imbalance by supplementing the dataset with a COVID dataset containing only fake articles/claims until there was a balance between the real and fake articles/claims. However, for these reasons, as was expected, we achieved different corpus and accuracy metrics.

The coherence of the LDA model for real news was 0.48 whereas the coherence for the LDA model for fake news was 0.29. At a significantly lower level, our perplexity scores were -7.39 and -7.62, respectively. It seems that datasets centering around specific matters propose their own behaviors. This is highlighted in that the COVID-19 related datasets, the LDA models do not mimic the models for the general dataset. Perhaps this is because there is much that is yet to be studied and reported about the novel virus, enabling a more varied range of topics.

Our two models for the COVID dataset achieved an overall accuracy of 92% and 93% (model 1 and model 2 respectively). Our distribution of true positives, false positives, false negatives, and true negatives for both models are as follows.

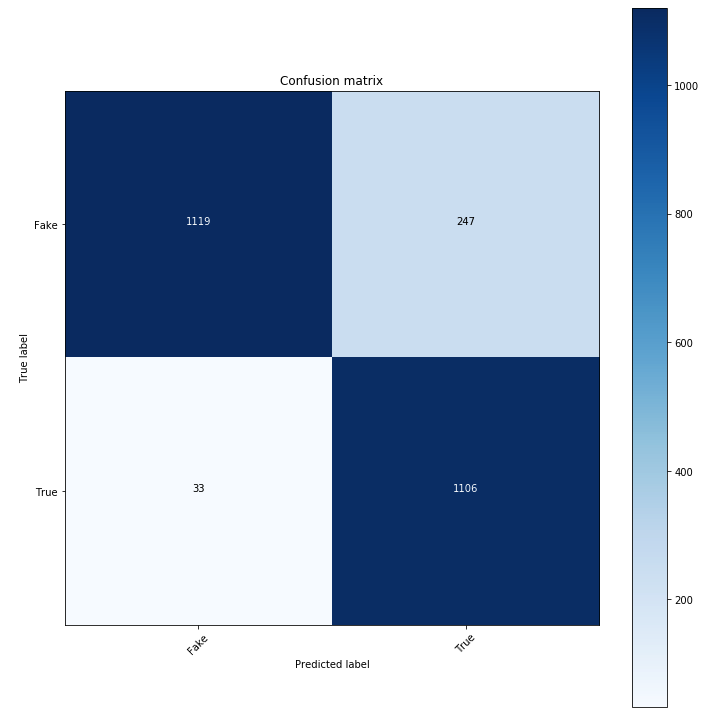

COVID Model 1

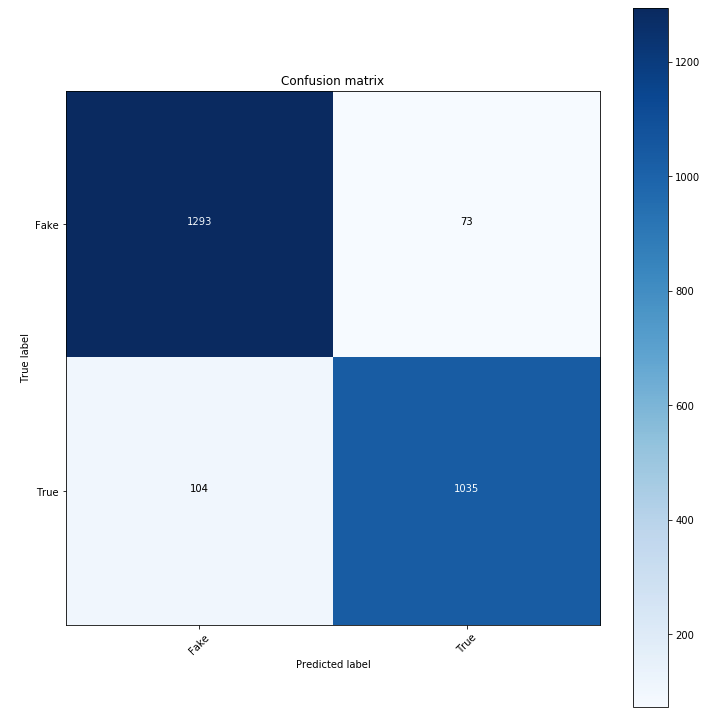

COVID Model 2

Model 1 misclassified 33 real news articles as fake news and 247 fake news articles as real news. Conversely, model 2 misclassified 104 real news articles as fake news and 73 fake news articles as real news. It is quite curious how each had relatively more issues with the opposite type of news – a repeated behavior in our iterations of rerunning the model.

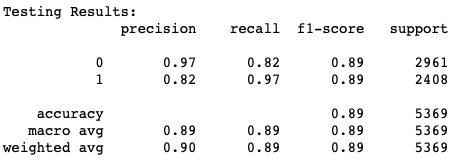

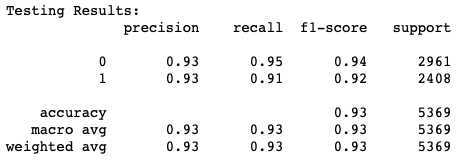

COVID Model 1

COVID Model 2

Based on these results, we can see that the model is better at detecting fake news than real news. Model 2, on the other hand, is equally as good at detecting fake news correctly as it is at detecting real news correctly. This behavior with the validation data is reflected with the testing data:

COVID Model 1

COVID Model 2

Both models achieved an incredible overall accuracy, 89% and 93% (model 1 and 2 respectively). So, what is clear is that the results of our classifiers demonstrate promise that a trained neural network can do a fabulous job at detecting fake news, but there are a few questions raised: how does our approach fair with other documented strategies? Is the system’s performance sufficient to justify its deployment? Let’s find out!

Relevant Considerations

Comparison to Other Datasets

As demonstrated with the COVID-19 dataset we used, a major bottleneck associated with automated fact-checking is the limited number of datasets. However, they are an indispensable component to the growth of fact-checking research as most fact- checking systems rely on machine learning tools.

During the task’s inception, datasets for fact-checking demonstrated positive signs towards a rigorous formulation of the fact-checking task. However, due to their small size, none were sufficient for training machine learning models. Since then, many datasets have been more fully constructed, deeming them more viable to train classifiers.

One such dataset is Wang’s Liar Liar, which compiles 12.8k human-labeled short statements from PolitiFact. Truthfulness ratings are assessed at 6 levels: pants-fire, false, barely-true, half-true, mostly-true, and true – and the classes are fairly balanced. The statements are sourced from various contexts, venues, topics, and speakers with meta-data on their affiliations, job, state, and even credit history. As a result of Wang’s experiments, it is suggested that the inclusion of meta-data in the input improves the accuracy slightly. The flaw of Liar, as Alhindi et al. points out, is that it does not include the evidence used by humans to judge a claim, limiting the capabilities of data-driven approaches that train on it.

Another dataset is Thorne et al.’s Fact Extraction and VERification (FEVER) dataset. It consists of 185,445 claims, each of which is labeled as ”Supported”, ”Refuted”, or ”NotEnoughInfo”. Included is the evidence that supports or refutes the claim – only in the case of the first two classes. The claims were extracted from Wikipedia, then altered and labeled by human annotators. The evidence sentences are collected during the labeling process. Along with the dataset release, the authors hosted the Fact Extraction and VERification (FEVER) Shared Task, which requires systems to provide not only the correct label but also the correct piece of supporting or refuting evidence. In 2018, the winning team achieved a score that is only about 6% lower than the state-of-the-art as of 2019, and the FEVER dataset has since been widely used to evaluate fact-checking systems in the past two years.

Another dataset is presented by Augenstein et al.. Their dataset consists of 34,918 claims from 26 English fact-checking websites. Each claim is accompanied by rich metadata and 10 evidence pages retrieved from Google search. Within each claim, entities such as people and places are also detected, disambiguated, and linked to their corresponding Wikipedia page.

Other Fact-Checking Methods

Claim Buster

Although not a fully automated system, ClaimBuster is an ongoing project towards assisted fact- checking that determines check-worthy claims to ease the burden of human fact-checkers (Hassan et al. (2017)). ClaimBuster models the fact-checking task as a supervised 3-class classification problem, where outputs are used to rank which sentences are check-worthy. 30 features are selected with a random forest classifier from a pool of features: sentiment, length, word, and POS tag, and Entity Type. The classification task achieves 74% and the ranking portion achieves 96% accuracy with Support Vector Machine(SVM). ClaimBuster’s creator used it on the 2015 GOP debate and had a good overlap with sentences checked by PolitiFact, CNN, and FactCheck.org. Hassan et al. tests whether subjectivity analysis would be able to discern between non-factual sentences, defined as subjective sentences (e.g. opinions, beliefs), but found no improvements in experimental results. Furthermore, Hassan et al. provide the current status of ClaimBuster which consists of the following components: Claim Monitor, it continuously monitors and retrieves texts from a variety of different sources; Claim Matcher, it gives an important factual claim within a repository of fact-checked claims; Claim Checker, it collects supporting or debunking evidence from knowledge bases and the web given a claim; And Fact Check Reporter, it synthesizes a report by combining the aforementioned evidence and delivers it to users. Overall, ClaimBuster presents a number of tools that are of great interest to automated fact-checking and the overall domain of computational journalism.

FakeBox

As of 2019, state-of-art fake news detector, Fakebox, does not include any sort of evidence seeking component (i.e. it does not provide evidence to back its assement of an article). Instead it analyzes linguistic characteristics of news articles from the headline to thecontent and inspects the site’s domain to compute a score (Zhou et al. (2019)). It reportedly achieves classification accuracy upwards of 95% (Zhou et al. (2019)). In their paper, Zhou et al. demonstrate how tampered real news articles can evade detection due to its stylistic resemblance to a real article. As a result, they propose evidence-based fact checking as a potential solution to address this vulnerability.

In contrast to the above, Rashkin et al. label their work as political fact-checking, not fake news detection. They divide their examination into two parts: a linguistic analysis of fake news and a truthfulness prediction model for political fact-checking. Of interest is their analysis of linguistic features. For example, first-person, second-person pronouns, and exaggerating words appear unusually more frequently in deceptive news. As for the prediction task, they experiment with Naive Bayes, Maximum Entropy, and LSTM (Long Short-Term Memory) using sequences of words as input. They also tried adding LIWC (Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count) features before the activation layer, but it shows little effect on the performance. The maximum top-3 ranking test accuracy for a 6-class classification was 22%, compared to 6% by the majority baseline.

What becomes clear is that although Fakebox achieved a high accuracy, sole reliance on linguistic characteristics and metadata comes with some flaws. Not only is the system susceptible to unintentional misinformation or machine generated fake news, but it also lacks the ability to justify its verdict of an article’s truthfulness.

Evidence Awareness with FEVER

Alhindi et al. extend Liar by extracting human justifications from fact-checking articles associated with the claim, with all verdict-identifying words removed to prove that the lack of evidence used by humans to judge a claim limits the capabilities of data-driven approaches that train on it. In fact, their experimental results show that additional contextual evidence improves the fact-checking prediction accuracy, pushing the significance of incorporating evidence even further.

Because purely linguistic approaches have limitations, and because the ability to provide facts to support their decisions is beneficial, most publishable fact-checking systems rely on evidence and are outlined as a multi-stage task with 3-4 subtasks. One of the earliest full-pipeline attempts at fact-checking was Thorne et al.’s proposed baseline for the FEVER dataset. Their system is comprised of three phases, all of which utilize existing NLP techniques and models. The three phases are document retrieval, sentence selection, and textual entailment recognition – which they define as the task of predicting whether the facts in the first sentence imply those in the second. The baseline algorithm achieves 31.87% accuracy for correct class and correct evidence, which is lower than 50.91% if a requirement for evidence is omitted.

Showing more promise is Yoneda et al.’s system which achieves a FEVER score of 62.52 – they also placed second at the first FEVER Shared Task! Their system compromises four phases: document retrieval, sentence retrieval, natural language inference, and aggregation-reranking. Error analysis suggests that the frequent failure cases are caused by similar word embeddings – in the context of NLP, it refers to the numerical vector representation of words – of unique information and complex sentences that require relationships between multiple words which is not captured by the alignment. More precise word embeddings that capture numerical features or are trained for the specific context are some viable solutions.

In the same year, Nie et al. present a system that placed first at the same FEVER Shared Task. In contrast to Yoneda et al.’s, Nie et al.’s system consists of three phases: document retrieval, sentence selection, and claim verification – fact extraction and verification. Noteworthy is that all three phases utilize a homogeneous 4-layer deep neural semantic matching network. the model does not utilize existing Natural Language Inference (NLI) models to obtain relationship between claims. Instead, in the third phase, the model is trained from scratch through a concatenation of word embeddings, normalized semantic relatedness scores from the initial two phases, ontological WordNet features, and additional embeddings to uniquely encode numbers. It achieves a 64.23 FEVER score and was the state-of-art at the time.

More recently, Soleimani et al. proposed a fact-checking system that utilizes Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT), one of the best pre-trained language models to date. The system consists of two BERT models: one for retrieving relevant evidence sentences and another for claim verification. In developing the models, the authors experiment with point-wise and pairwise approaches in finetuning BERT, and both outperform most existing systems in recall. In addition, they also examine the effect of Hard Negative Mining (HNM)in the evidence retrieval BERT model and found that it slightly improves the system’s performance. Through their experiments on the FEVER dataset, the pipeline achieves an almost-state-of-art FEVER score of 69.66.

DREAM

Zhong et al. presents the state-of-art fact checking model, abbreviated as “DREAM”, which achieves 70.60 FEVER score and 76.85% label accuracy. The DREAM system is able to do so because it utilizes a graph-based approach to connect and reason about multiple pieces of evidence. It shares the same 3-stage system components as the baseline proposed by Thorne et al.. Inter- estingly, the document retrieval component mostly follows Nie et al.’s approach, and the sentence selection component is framed as a semantic matching problem extending from pre-trained language models. What’s unique about their approach is the claim verification component. It uses semantic structures of the evidence instead of simple string or feature concatenation. In doing so, it adopts a graph structure to capture relative distances between words allowing it to measure how seman- tically related they are. Thereafter, it takes advantage of graph convolutional and graph attention networks to propagate and aggregate information on the graph. Despite the added layers, the model is not without any faults. In the error analysis, Zhong et al. list that the frequent sources of errors are failures to match different phrases that refer to the same thing in the particular context, and misleading evidences retrieved from the earlier stages. Nevertheless, DREAM’s performance suggests that graph-based approaches lead to some of the best performances among fact-checking systems.

What becomes clear is that the accuracy of a system is not enough to justify the deployment of a fact-checking and classification system. Indeed a high accuracy is attractive to any developer, but there are numerous issues that the scholarly community is addressing: from ranking claims based on check-worthiness to vulnerability to machine-generated fake news, and even basing assessment on the amount of supporting or refuting evidence.

Challenges

A Twin Challenge

Recently, Nakov et al. (2021) outline two challenges towards automated fact-checking: first, to develop practical tools to solve the problems trained fact-checkers face; second, to demonstrate the value of their tools to trained fact-checkers in their daily work. Fact-checking is not a straight- forward or routine process. It requires a series of steps that range from determining check-worthy claims to assessing the truthfulness of a claim. Nakov et al. lists that the areas where fact-checkers believe technology can help. They are: finding claims worth fact-checking, detecting previously fact-checked claims, evidence retrieval, and automated verification. Even though many tools have been developed to address these areas, there are still limitations to both the manual and automated process of fact-checking that warrant human fact-checkers’ apprehension. For automated systems, establishing credibility can prove problematic as some system’s do not always provide supporting evidence for their assessments. And for the manual task of fact-checking, scalability is a lingering issue. It is no surprise, then, that collaboration between professional fact-checkers and researchers is principal to the development of robust automated fact-checking systems. This bears relevant consideration as automated fact-checking tools and research expand, introducing new challenges and impacts on real-world fact-checking.

Technological Limitations

Like most machine learning and deep learning models, most state-of-art fake news detection systems rely on data that could be easily converted into a vector and fed to the model such as metadata and word embeddings. However, this approach is vulnerable to certain types of fake news, such as machine-generated fake news due to their stylistic similarities to real news, as demonstrated by Schuster et al. and Zhou et al.. Because fact-checking attends to the truthfulness of a claim, sourcing relevant information from a repository is unavoidable. As is the case with the three-stage systems used by Thorne et al. and Nie et al., the system begins with document retrieval and end with fact verification, relying on very different techniques from various areas of computer science. Of interest is evidence retrieval which appears to be most problematic. This is evident in DREAM which achieves some of the best performance to date and helps identify poor performance in the evidence retrieval component(s) as a source of inaccuracies. Also noteworthy is that FEVER, the dataset used to evaluate DREAM, limits the justification for its assessment to sentences from Wikipedia. In doing so, the FEVER dataset controls the number of sources to pull from, and implicitly assumes that all sentences from Wikipedia can be trusted. This is much unlike the rationale produced by human fact-checkers. Therefore, expanding the knowledge base and classifying reliable sources are two more areas that fact-checking systems need to address before deployment.

Ethical Concerns

While the benefits of accurate fact-checking systems are obvious, there are also some practical concerns that deserve attention. Relevant is the question: What are the consequences of deploying automated fact-checking systems?

Important to understanding the possible consequences of deploying automated fact-checking systems is exploring how real-life people interact with such systems. Nguyen et al. explores this through their examination of user interactions with AI fact-checking systems. Nguyen et al.’ system is a transparent and interactive human-AI interface that helps users assess whether to trust the system’s decision or not. Through their user study that asks participants to use the system to aid their personal assessment of a claim’s truthfulness, Nguyen et al. observe that the system can be both helpful and misleading. Particularly concerning is that the user’s accuracy improve on statements that are correctly classified and falls on statements that are incorrectly classified. In other words, when the system is right, people learn from it and make better predictions. And when the model is wrong, people sometimes make wrong predictions as well. What is clear is the following: On the one hand, fact-checking tools could increase an individuals accuracy in deciding whether to trust a claim; on the other hand, it runs the risk of reducing an individual’s exercising of personal judgment should the tool makes systematic mistakes.

Another issue is raised by Oshikawa et al.. While one could argue that meta-data helps the accuracy in fact-checking and fake news detection, it is wise to consider the problematic nature of a fact-checking system’s assessment of a claim’s source – e.g. the person, news network, organization. This is even more clear in the case of determining whether something is truthful based on the claim’s author. For example, a system may learn to attach high trustworthiness to prominent political figures or reputable news sources; consequently, this could lead to the silencing of less prominent but reputable voices. In a similar venue, the question of who is accountable for a system’s errors is brought into the spotlight. Nguyen et al. and Oshikawa et al. address two different yet equally valid points. As is the case with any of machine learning tool, the creators of automated fact-checking systems are responsible for detecting and minimizing bias in their systems. However, users bear some responsibility in using these tools as aids to help (not replace) their ability to judge claims.

Reflection

Since its inception, this project has taken many circuitous routes with regard to how we should develop our networks, what datasets are to be used, and what our end goal should be. As is the nature of journalism, our process was messy, however, afforded immense insight into the pertinent challenge that is automated fact-checking.

Going back to our thesis, we had initially sought out to address the lack of oversight in quality filters on social media and the consequential spread of COVID misinformation. This goal was a well-intentioned desire, though, as we have learned throughout this project, was not simple given our current resources and time constraints. As was discussed in the sections above, we learned that the datasets we were provided were a major bottleneck in our experiment given their less sophisticated nature relative to other datasets that were not only larger but passed their judgment along scales of truthfulness as opposed to a true-false dichotomy. Additionally, we have learned how our metric of accuracy is almost deceptive in its characterization of our classifiers given how it eclipses other pertinent properties of the networks such as how vulnerable they are to machine-generated fake news and whether they can provide evidence to substantiate their verdicts.

These complications in our project, let alone the ethical oversights, have thoroughly revised our understanding of what is required to complete our initial thesis and have therefore strongly informed what we would want to do differently next time.

Firstly, we would allocate more time to finding and/or developing a dataset that reflects the inherent levels of truthfulness in claims, moreover pulls from more expansive sources that are diverse in their nation of publication, publicity, writing style, topic, and author. In doing this, we’ll address a major concern in automated fact checking that is the censorship of less prominent, yet reputable voices. Additionally, we would heed the danger that is the outsourcing of human trustworthiness assessments to artificial intelligence, and make an effort to collaborate with trained fact-checkers to ensure that our work and goals enhance and overlap with theirs.

Indubitably, these are only a fraction of the many critical (and unknown) steps that need to be taken to ensure automated fact-checking is an equitable and sustainable process in journalism. It is our hope that, over time, more people, not just developers and their classifiers, will aid in taking these steps and ultimately designing a more trustworthy world. Certainly, training for trust is not a task unique to our neural networks, but one we should all embrace as a society that constantly introduces nuance into what is trustworthy, and as developers who must act per that change.

Related Works

For a more comprehensive look at the resources that inform our work, please refer to our literature review.

- Alhindi, T., Savvas Petridis, and Smaranda Muresan. Where is your evidence: Improving fact- checking by justification modeling. In Proceedings of the First Workshop on Fact Extraction and VERification (FEVER), pages 85–90, 2018.

- Augenstein, I., Christina Lioma, Dongsheng Wang, Lucas Chaves Lima, Casper Hansen, Christian Hansen, Jakob Grue Simonsen . MultiFC: A Real-World Multi-Domain Dataset for Evidence-Based Fact Checking of Claims. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (EMNLP-IJCNLP), pages 4677–4691, nov 2019. URL http://arxiv.org/abs/1909.03242.

- Baly, R., Mitra Mohtarami, James Glass, Lluis Marquez, Alessandro Moschitti, and Preslav Nakov. Integrating stance detection and fact checking in a unified corpus. In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguis- tics: Human Language Technologies, pages 21–27, 2018.

- Cohen, S., Chengkai Li, Jun Yang, and Cong Yu. Computational journalism: A call to arms to database researchers. In 5th Biennial Conference on Innovative Data Systems Research, CIDR, pages 148–151, 2011.

- Ding, Lixuan, Lanting Ding, and Richard O. Sinnott. “Fake News Classification of Social Media Through Sentiment Analysis.” International Conference on Big Data. Springer, Cham, 2020.

- Hassan, N., Fatma Arslan, Chengkai Li, and Mark Tremayne. Toward automated fact- checking: Detecting check-worthy factual claims by claimbuster. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, KDD ’17, page 1803–1812, New York, NY, USA, 2017. Association for Computing Machinery. ISBN 9781450348874. doi: 10.1145/3097983.3098131. URL https://doi.org/10.1145/3097983. 3098131.

- Hamid, Abdullah, et al. “Fake News Detection in Social Media using Graph Neural Networks and NLP Techniques: A COVID-19 Use-case.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2012.07517 (2020).

- Kaliyar, Rohit Kumar, et al. “FNDNet–a deep convolutional neural network for fake news detection.” Cognitive Systems Research 61 (2020): 32-44.

- Le, Thai, Suhang Wang, and Dongwon Lee. “Malcom: Generating malicious comments to attack neural fake news detection models.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2009.01048 (2020). URL: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2009.01048.pdf

- Nakov, P., David Corney, Maram Hasanain, Firoj Alam, Tamer Elsayed, Alberto Barron- Cede, Paolo Papotti, Shaden Shaar, and Giovanni Da San Martino. Automated fact-checking for assisting human fact-checkers. In EURECOM, editor, Submitted to ArXiV, 13 March 2021, 2021.

- Nguyen, A., Aditya Kharosekar, Saumyaa Krishnan, Siddhesh Krishnan, Elizabeth Tate, By- ron C. Wallace, and Matthew Lease. Believe it or not: Designing a human-ai partnership for mixed-initiative fact-checking. In Proceedings of the 31st Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology, UIST ’18, page 189–199, New York, NY, USA, 2018. Asso- ciation for Computing Machinery. ISBN 9781450359481. doi: 10.1145/3242587.3242666. URL https://doi.org/10.1145/3242587.3242666.

- Nie, Y., Haonan Chen, and Mohit Bansal. Combining fact extraction and verification with neural semantic matching networks. CoRR, abs/1811.07039:6859–6866, 2018. URL http://arxiv.org/ abs/1811.07039.

- Oshikawa, Ray, Jing Qian, William Yang Wang. A Survey on Natural Language Processing for Fake News Detection. In Proceedings of the 12th Language Resources and Evaluation Conference, pages 6086–6093, nov 2018. URL http://arxiv.org/abs/1811.00770.

- Rashkin, H., Eunsol Choi, Jin Yea Jang, Svitlana Volkova, and Yejin Choi. Truth of varying shades: Analyzing language in fake news and political fact-checking. In Proceedings of the 2017 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, pages 2931– 2937, Copenhagen, Denmark, September 2017. Association for Computational Linguistics. doi: 10.18653/v1/D17-1317. URL https://www.aclweb.org/anthology/D17-1317.

- Schuster, Tal, Darsh J Shah, Yun Jie Serene Yeo, Daniel Filizzola, Enrico Santus, Regina Barzilay. Towards Debiasing Fact Verification Models. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (EMNLP-IJCNLP), pages 3410–3416, 2019. ISBN 9781950737901. doi: 10.18653/v1/d19-1341. URL https://arxiv.org/pdf/1908.05267.pdf.

- Soleimani, A., Christof Monz, and Marcel Worring. BERT for evidence retrieval and claim verification. CoRR, abs/1910.02655, 2019. URL http://arxiv.org/abs/1910.02655.

- Tan, Reuben, Kate Saenko, and Bryan A. Plummer. “Detecting Cross-Modal Inconsistency to Defend Against Neural Fake News.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2009.07698 (2020). URL: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2009.07698.pdf

- Thorne, James and Andreas Vlachos. Automated Fact Checking: Task Formulations, Methods and Future Directions. In Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Computational Linguistics, pages 3346–3359, jun 2018. URL http://arxiv.org/abs/1806.07687.

- Vlachos, A., Sebastian Riedel. Fact checking: Task definition and dataset construction. In Proceedings of the ACL 2014 Workshop on Language Technologies and Computational Social Sci- ence, pages 18–22, Baltimore, MD, USA, June 2014. Association for Computational Linguistics. doi: 10.3115/v1/W14-2508. URL https://www.aclweb.org/anthology/W14-2508.

- Wang, William Yang. ”liar, liar pants on fire”: A new benchmark dataset for fake news detection. In Proceedings of the 55th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 2: Short Papers), pages 422–426, 2017.

- Yoneda, T., Jeff Mitchell, Johannes Welbl, Pontus Stenetorp, and Sebastian Riedel. UCL machine reading group: Four factor framework for fact finding (HexaF). In Proceedings of the First Workshop on Fact Extraction and VERification (FEVER), pages 97–102, Brussels, Belgium, November 2018. Association for Computational Linguistics. doi: 10.18653/v1/W18-5515. URL https://www.aclweb.org/anthology/W18-5515.

- Zhong, W., Jingjing Xu, Duyu Tang, Zenan Xu, Nan Duan, Ming Zhou, Jiahai Wang, and Jian Yin. Reasoning over semantic-level graph for fact checking. CoRR, abs/1909.03745, 2019. URL http://arxiv.org/abs/1909.03745.

- Umer, M., Z. Imtiaz, S. Ullah, A. Mehmood, G. S. Choi and B. -W. On, “Fake News Stance Detection Using Deep Learning Architecture (CNN-LSTM),” in IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 156695-156706, 2020, doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3019735.

- Zhou, Z., Huankang Guan, Meghana Bhat, and Justin Hsu. Fake news detection via nlp is vulnerable to adversarial attacks. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence. SCITEPRESS - Science and Technology Publications, 2019. ISBN 9789897583506. doi: 10.5220/0007566307940800. URL http://dx.doi.org/10.5220/ 0007566307940800.